- Home

- Tudor Robins

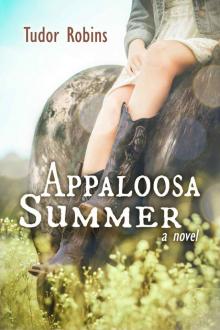

Appaloosa Summer (Island Trilogy Book 1)

Appaloosa Summer (Island Trilogy Book 1) Read online

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

About the Author

Objects in Mirror

Acknowledgments:

Appaloosa Summer

By

Tudor Robins

Island Trilogy – Book One

Copyright 2014 Tudor Robins

This e-book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This e-book may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you’re reading this book, and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination, or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, events, or locales, is entirely coincidental.

Robins, Tudor, 1972 –

Appaloosa Summer / Tudor Robins

Ebook.

ISBN 978-0-9936837-1-8

Editor: Hilary Smith

Proof-reader: Gillian Campbell

Cover photograph: Kacy Hurlbert Todd / Boss Mare Photography

Front cover design: Allie Gerlach

Spine / back cover / interior design: Cheryl Perez www.yourepublished.com

Website: Lynn Jatania / Sweet Smart Designs

Author photo: Debora Dekok

Tudor Robins gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the City of Ottawa.

Also by Tudor Robins

Objects in Mirror

Chapter One

I’m staring down a line of jumps that should scare my brand-new show breeches right off me.

But it doesn’t. Major and I know our jobs here. His is to read the combination, determine the perfect take-off spot, and adjust his stride accordingly. Mine is to stay out of his way, and let him jump.

We hit the first jump just right. He clears it with an effortless arc, and all I have to do is go through my mental checklist. Heels down. Back straight. Follow his mouth.

“Good boy, Major.” One ear flicks halfway back to acknowledge my comment, but not enough to make him lose focus. A strong, easy stride to jump two, and he’s up, working for both of us, holding me perfectly balanced as we fly through the air.

He lands with extra momentum; normal at the end of a long, straight line. He self-corrects, shifting his weight back over his hocks. Next will come the surge from his muscled hind end; powering us both up, and over, the final tall vertical.

It doesn’t come, though. How can it not? “Come on!” I cluck, scuff my heels along his side. No response from my rock solid jumper.

The rails are right in front of us, but I have no horsepower – nothing – under me. By the time I think of going for my stick, it’s too late. We slam into several closely spaced rails topping a solid gate. Oh God. Oh no. Be ready, be ready, be ready. But how? There’s no good way. There are poles everywhere, and leather tangling, and dirt. In my eyes, in my nose, in my mouth.

There’s no sound from my horse. Is he as winded as me? I can’t speak, or yell, or scream. Major? Is that him on my leg? Is that why it’s numb? People come, kneel around me. I can’t see past them. I can’t sit up. My ears rush and my head spins. I’m going to throw up. “I’m going to…”

**********

I flush the toilet. Swish out my mouth. Avoid looking in the mirror. Light hurts, my reflection hurts, everything hurts at this point in the afternoon, when the headache builds to its peak.

Why me?

I’ve never lost anybody close to me. My grandpa died before I was born, and my widowed grandma’s still going strong at ninety-four. She has an eighty-nine-year-old boyfriend. They go to the racetrack; play the slots.

If I had to predict who would die first in my life, I would never, in a million years, have guessed it would be my fit, strong, seven-year-old thoroughbred.

Never.

But he did.

Thinking about it just sharpens the headache, so I press a towel against my face, blink into the soft fluffiness.

“Are you OK?” Slate’s voice comes through the door. With my mom and dad at work, Slate’s been the one to spend the last three days distracting me when I’m awake, and waking me up whenever I get into a sound sleep. Or that’s what it feels like.

“Fine.” I push the bathroom door open.

“Puke?”

I nod. Stupid move. It hurts. Whisper instead. “Yes.”

“Well, that’s a big improvement. Just the once today.”

She follows me back to my room. She’s not a pillow-plumper or quilt-smoother – I have to struggle into my rumpled bed – but it’s nice to have her around. “I’m glad you’re here, Slatey.” I sniffle, and taste salt in the back of my throat.

I’m close to tears all the time these days. “Normal,” the doctor said. Apparently tears aren’t unreasonable after suffering a knock to the head hard enough to split my helmet in two, with my horse dropping stone cold dead underneath me in the show ring. I’m still sick of crying, though. And puking, too.

“Don’t be stupid, Meg; being here is heaven. My mom and Agate are going completely over the top organizing Aggie’s sweet sixteen. There are party planning boards everywhere, and her dance friends are always over giggling about it too.”

“Just as long as it’s not about me. I don’t want to owe you.”

“’Course not; you’re not that great of a best friend.”

The way I know I’ve fallen asleep again, is that Slate is shaking me awake. Again.

“Huh?” I open one eye. Squinting. The sunlight doesn’t hurt. In fact, it feels kind of nice. I open both eyes.

“Craig’s here.”

I struggle to get my elbows under me, and the shot of pain to my head tells me I’ve moved too fast.

“Craig?”

She’s nodding, eyes wide.

“Like our Craig?”

“Uh-huh.”

First my mom canceled her business trip scheduled for the day after the accident; now our eighty-dollar-an-hour, Level Three riding coach is at my house. “Are you sure I’m not dying, and you just haven’t told me?”

“I was wondering the same thing.”

“What am I wearing?” I blink at cropped yoga pants and a t-shirt I got in a 10K race pack. It doesn’t really matter – I’ve never seen Craig when I’m not wearing breeches and boots; never seen, or even imagined him in the city – changing clothes is hardly going to make a difference.

Slate leads the way down the stairs, through the hallway and into the kitchen, where Craig’s shifting from foot to foot, reading the calendar on the fridge. He must be bored if he wants the details of my dad’s Open Houses, my mom’s travel itinerary.

“Smoking,” Slate whispers just before Craig turns to me. And, technically, she’s right. His eyes are just the right shade of em

erald, surrounded by lashes long enough to be appealing, while stopping short of girly. His cheekbones are high and pronounced, just like his jawbone. And his broad, tan shoulders, and the narrow hips holding up his broken-in jeans are the natural trademarks of somebody who works hard – mostly outside – for a living.

But he’s our riding coach. Craig, and our fifty-five year old obese vice-principal (with halitosis), are the two men in the world Slate won’t flirt with. I don’t flirt with him, mostly because I’ve never met a guy I like more than my horse. Major …

“Hey Meg.” Craig’s quiet voice is a first. The gentle hug. He steps back, eyes searching my head. “Do you have a bump?”

I take a deep breath and throw my shoulders back. “Nope.” Knock my knuckles on my temple. “All the damage is internal.”

Craig’s brow furrows. “Meg, you can tell me how you really feel.” No I can’t. Of course I can’t. Even if I could explain the emptiness of losing my three-hour-a-day, seven-day-a-week companion, the guilt at “saving” him from the racetrack only to kill him in the jumper ring, and the take-it-or-leave-it feeling I have about showing again, none of that is conversation for a sunny springtime afternoon.

Still, I can offer a bit of show and tell. “I have tonnes of bruises. And I’ve puked every day so far. And, this is weird but, look.” I use my index finger to push my earlobe forward. “My earring caught on something and tore right through.”

The colour drains from Craig’s face, and now I think he might puke.

“Meg!” Slate pokes me in the back. “Sit down with Craig and I’ll make tea.”

Craig pulls something out of his pocket, places it on the table. A brass plate reading “Major”. The one from his stall door. “We have the rest of his things in the tack room. We put them all together for you.”

Yeah, because you wanted to rent out the stall. I can’t blame him. There’s a massive waiting list to train with Craig. And my horse had the consideration to die right at the beginning of the show season. Some new boarder had her summer dream come true.

I reach out; turn the plaque around to face me. Craig’s trained me too well – tears in one of his lessons result in a dismissal from the ring – so now, even with a concussion, I can’t cry in front of him. Deep breath. I rub my thumb over the engraved letters M-A-J-O-R. “There was nothing that horse couldn’t do.”

Craig sighs. “You’re right. He was one in a million. Have you thought about replacing him?”

Chapter Two

A week passes in a strange limbo. I’m mostly better – but if I try to read for more than a couple of minutes, my lurking headache presses back in, so no school yet. I don’t feel nauseous, but when I take our dog Chester out, and run to catch up with him, I’m left doubled over and dizzy.

I appreciate it when Slate comes to see me after riding on Wednesday. While Chester’s delighted to have me home, I’m not sure talking to a dog all day is great for my mental health.

The day’s warm, breezy; perfect for riding. “How was it?” I ask.

“Good, OK, fine.”

“You don’t have to hold back for me, you know. You can tell me it was great.”

“Oh, my-one-and-only-Meg, I would tell you if it was great. It wasn’t. It was fine. It’ll only be great when you’re back.”

Every single day I’m tempted to go back, but then I imagine being a sad, sort of shadow person drifting around aimlessly. A rider without a horse. Until I’m well enough to ride, I don’t belong at the barn.

I deflect. “Tell me the barn gossip.”

“Um, well, there are two new grey ponies – one’s an uber-expensive boarder, and one’s a new pony Craig bought for the school – and you can’t tell them apart. To the point where some intermediate rider rode the boarder’s pony by mistake, and Craig only figured it out halfway through the lesson, when the school pony stuck his head over the field gate and whinnied.

Oh, and the new wash stall is ready, and the barn cat had kittens, and Major’s stall is filled.”

“Major’s stall?”

She puts her hand on my shoulder. “Is that OK, Meggie? I thought if I said it fast, with everything else, it might be better.”

I think for a minute. I didn’t realize how much the spectre of that gaping empty stall was bothering me – how, when I thought of the barn, it was all I could picture. Now, Slate’s removed it. I take a deep breath. “You know what? It is OK. It’s fine. And, I’m going to the doctor’s tomorrow morning. If he says I can ride, I’ll come out with you in the afternoon.”

“You will?”

“I will.”

It doesn’t feel like ten days have passed. The drive to the barn feels just the same. The tires hum on the highway, roll on the pavement of the concession road, crunch as gravel takes over. We pass through dense trees, then move into open farmland bounded with barbed wire, and finally hit the neat white wooden fences marking the edge of Craig’s property.

Slate’s in the backseat beside me, just like she has been so many times over the years, and, as usual, our helmets are tumbled on the seat between us. The difference is, where hers is scuffed and scratched, mine’s brand-new; without a mark on it – “It’s a welcome-back-to-riding gift,” Slate told me as she handed it over. “Plus, you’d probably get lice if you borrow one from the schooling stash.”

Another change; instead of waving and driving away when we reach the barn, my mom steps out and stretches.

“Emily!” Craig is grace and charm to the moms – the cheque-payers. He air kisses my mother. “It’s been too long.”

“Meg said you came to visit. I’m sorry I missed you; meetings, you know. It was so kind of you to drive all the way into the city when you’re so busy.”

“It was the least I could do …”

While they chat, and while Slate puts on her half-chaps with the fiddly zippers that take forever, I turn away and walk to the barn. If I want to be alone when I see Major’s stall with a new horse in it, I need to move fast.

I throw my shoulders back, take a deep breath, and step into the filtered light of the aisle. Blink twice, sneeze at the dust motes floating through the air, and turn left, to walk the twenty steps to the most familiar box stall in the stable.

The words are right there, on the tip of my tongue: “Hey Buddy.” It’s a phrase I’ve spoken hundreds of times over the last two years. But, at the last minute, I change them for “Hey Sweetie.” Because the delicate head poking over the half door, with its bright long-lashed eyes, and near-perfect star, has to belong to a mare.

I step back to read her nameplate. “Little Rich Girl.” So, yes, a mare.

She reaches her nose out, snuffles around my shoulders and face. She’s gentle, her muzzle like moleskin, whiskers carefully trimmed. Groomed for the show ring. Which, of course, she would be. People don’t pay Craig’s prices unless they intend to compete.

She rests her face flat against my breastbone, and I reach to scratch behind her ears. She exhales a long, shuddering breath, warm and soft against my t-shirt.

I smooth a rogue chunk of mane to the left side of her neck. “This is a good stall. You’ll like it here.” I waited months for this stall to come free for Major. I wanted the internal window for him; the one where the barn cat sits and cleans her paws. I wanted him to have cross ties right outside his door so he’d never be bored. I’ve mucked this stall out for him, groomed him in this stall and, once, at the end of a very long day, fell asleep slumped in the corner of this stall while I waited for Major to finish the bran mash I’d made for him.

It’s not Major’s stall any more. A tear plunks on the mare’s bright chestnut face and I blink to stop any more from falling.

“You OK?” Craig’s at the far end of the aisle.

“Uh-huh.” I whisk my thumb over the drop; press it into nothing more than a dark spot among the surrounding hairs. By the time Craig reaches my side, it’s disappeared.

“I wanted you to know it all went OK with the … uh …

arrangements … for Major.”

“Oh. Thanks. It felt like the right thing to do.” It felt like a surreal thing to do, actually, when I was presented with the option of donating Major’s body to a nearby big cat sanctuary. “Because he died without being euthanized, it would be safe for the cats,” the vet explained.

For the cats to eat, she meant. Weird at first, but burying, or cremating something as big as a horse is more complicated than you might think, and the idea of having him rendered into glue was awful. By comparison, nature taking its course – some carnivores eating a herbivore – seemed much better.

The hunk of Major’s mane sitting in my bedside table – the one I grabbed when he went down, and I fell off – is more important than his flesh and muscle.

Craig clears his throat. “I was wondering if you’d like to ride Apollo?”

Craig’s warmblood jumper, imported from Europe; so expensive he’s owned by a syndicate.

“I’d have to be worse than concussed to say no to that.”

His brow furrows. “You are OK, right? It’s safe to ride?”

“The doctor cleared me this morning. As long as I don’t jump.”

I don’t tell Craig about the doctor’s wagging finger, and his deep sigh, and his warning, “This is against my better judgment.”

Craig beams. “Great! I’ll pull his tack out for you.”

As I grab a lead shank, and go to get Apollo out of his rubber-padded stall, there’s something else I’m not telling Craig either. How can I explain that I feel only flat indifference about riding his super-star horse that’s worth about five times more than any other I’ve ever been on?

I’m sure it will change once I get in the saddle.

**********

Apollo feels like the sixty-thousand dollars he’s rumoured to have cost. Where Major was whippy, stringy, this horse is rock hard everywhere: under my legs as I squeeze him, under my hands as I stroke his neck. It’s like riding one big muscle. He punches the ground in his walk, and his trot nearly launches me out of the saddle with each stride.

Appaloosa Summer (Island Trilogy Book 1)

Appaloosa Summer (Island Trilogy Book 1)